|

Figure 1. Internationally Recognized Administrative Divisions, 1990

|

Figure 2. Locally Recognized Administrative Divisions, 1990

IN MID-1992 UGANDA WAS still trying to recover from two decades of instability and civil war. For the majority of the population born after Idi Amin Dada seized power in 1971, a peaceful and prosperous Uganda was difficult to imagine. But many Ugandans saw promising signs of economic and political reform in the nation's fledgling grass-roots democracy, new economic development projects and export initiatives, and the renewed commitment to education and social services. Serious problems remained unresolved, however, and it was clear that efforts to rehabilitate Uganda's devastated economy and return the country to civilian rule would take most of the decade.

Uganda in earlier times had known periods of relative peace, but not quiet isolation. Its early history, told through the archaeological record and accounts of travelers, included centuries of political change, population migration, and the development of cultural diversity. The earliest occupants of the low-lying plateau that stretches north from the shores of Lake Victoria had been joined by new migrants from the north and west by about the fourth century A.D. These new arrivals, ancestors of today's Bantu-speaking societies, came under pressure from the expansion of non-Bantu speaking warriors and herders from the northeast by about the tenth century A.D. The gradual population movement to the southwest was slowed by the formation of new societies comprising farmers and herders. Several of them competed for regional control, assimilating and dominating their neighbors to varying degrees, and several evolved into complex centralized societies marked by economic and social stratification. During the nineteenth century, the strongest among them, Bunyoro, began to lose power to its breakaway neighbor, Buganda. By the end of the nineteenth century, Buganda dominated the region, but the rivalry between Buganda and Bunyoro remained strong enough to be exploited by colonial agents who established the Uganda Protectorate in 1894.

Representatives of Islam and Christianity, who had also competed for social, spiritual, and economic advantage over one another, also left a lasting imprint on Ugandan society. Political developments throughout the twentieth century have reflected the divisions between Uganda's centralized and noncentralized societies, and among the diverse ethnic groups in each of these categories, their different responses to the colonial experience, and the impact of world religions.

Uganda had been brought into the world economic system gradually over the centuries, first through trade in ivory, and later through trade in slaves and agricultural products. In the early twentieth century, colonial officials, with the help of Baganda (people of Buganda; sing., Muganda) agents, established cash crops, especially cotton, and later coffee, to help finance economic development according to world market demands. Buganda prospered and drew farm workers from other areas of the protectorate. Buganda's schools also developed ahead of those in other regions, helping fuel existing rivalries between the Baganda and their neighbors.

Agricultural production increased dramatically during World War I, and during the 1920s and 1930s, farmers were able to weather the fluctuations in world market prices by cutting cash- crop production and reverting to subsistence agriculture. Protectorate laws carefully regulated the use of land and other resources, often allocating economic rights according to racial categories. Protests against such restrictions increased after World War II, but unlike much of Africa, Uganda was preparing peacefully for independence well before it arrived.

At independence in October 1962, ethnic and regional rivalries were crystallized in several newly formed political parties and in the federal system that gave substantial autonomy to the four large kingdoms in the south, plus the highly centralized society of Busoga. The central government maintained control over the northern region. The army flourished under the first independent government led by Milton Obote and pressed its demands for higher pay and improved conditions of service. A military coup in 1971, however, plunged Uganda into eight years of terror and disintegration under the government of Idi Amin. Uganda's once-developing economy disintegrated, and its once- thriving education system suffered lasting damage. Government- sanctioned brutality became commonplace. Many of Uganda's intellectuals and entrepreneurs were forced to flee. A brief but tumultuous political transition followed the nightmare of the Amin years, and the early 1980s became a time of revenge-seeking and despair under the second government led by Milton Obote. Growing rebellions finally forced Obote from office in 1985, but Ugandans had little cause for confidence in their political future.

The government led by Yoweri Kaguta Museveni that seized power in January 1986 had not inspired overwhelming public confidence in its ability to rule. Museveni's National Resistance Army (NRA), however, had shown greater military discipline than other armed forces in recent years, and Museveni declared that establishing a peaceful and secure environment was his highest priority as president. For this goal, Museveni had strong popular backing.

The NRA's hastily formed political arm, the National Resistance Movement (NRM), set out its political program in the Ten-Point Program, which advocated a broad-based democracy and a hierarchy of popular assemblies, or resistance councils (RCs), from the village through district levels to mediate between the national government and the village. After initial doubts about embracing Western economic reforms, the NRM also embarked on ambitious structural adjustment and export diversification programs. Museveni took seriously the notion of accountability in government service and set about improving standards of behavior among public sector employees.

But the NRM had few politically educated people in its ranks, and Museveni's policy of appointing members of previous governments to high office cost him political support. In addition, the NRM's political ideas were new and lacked support in the northern and eastern regions, where popular insurgencies continued to plague his rule even after six years in power. And the army, with its intense recruitment drives and policy of incorporating former rebel opponents into its ranks, was unable to eliminate the human rights abuses for which it had become infamous. Campaigns to pacify and stabilize rebel-occupied areas turned into army assaults on peaceful residents of the north and east, and the judicial system was slow to deal with those accused of serious atrocities. At the same time, the cost of maintaining the military escalated rapidly, and pressures to reduce the size of the army posed the dilemma of escalating unemployment among former members of the military.

Since research on this volume was completed in 1990, the government has continued its program of political reform in an effort to meet its own deadline for returning to civilian rule by 1995. Progress, however, has been slow. The central institutions of grass-roots democracy, the RCs, improved their ability to function as part of the government, but in some areas the RCs' exact responsibilities were not well understood. In a few cases, their efforts to maintain order degenerated into vigilantism.

A twenty-one member constitutional commission appointed in 1988 completed its nationwide consultations in late 1991, but it postponed submitting a draft constitution to the government until November 1992. The government also planned a nationwide referendum on the draft constitution in mid-1993.

Nationwide RC elections, held from February 29 to March 9, 1992, were generally considered a success. Voters in more than 30,000 villages elected RCs for their villages, and indirect elections were held for RC members at the parish, subcounty, county, and district levels. Partisan campaigning and explicitly soliciting votes were legally prohibited; candidates who violated this prohibition were disqualified, although candidates were able to use other avenues to make their views known. In several areas, staunch critics of the government were elected to the RCs, confirming the widespread belief that the elections were generally free and fair. About half of the incumbent RC members were removed from office, and several members of the national legislature lost in elections for village RCs.

In a few areas, such as Bushenyi, elections were delayed because of conditions caused by religious feuding, political violence, or the spreading drought. In a few localities, election irregularities led to the annulment and rescheduling of the balloting. But when the votes were counted, more than 400,000 Ugandans had been elected to various levels of political office, and the new office-holders represented nearly every ethnic, religious, and political identity in the country. The next elections were planned for late 1994, when the government pledged it would provide secret ballots and the direct election of legislators at all levels.

Despite well-publicized human rights abuses by the military that continued through early 1991, President Museveni's New Year's message for 1992 emphasized his commitment to improving this record. By mid-1992, the courts had begun to hear the cases of eighteen prominent northern politicians who had been accused of treason in April 1991, and charges against several of the accused had been dropped. The government had disciplined soldiers for human rights abuses in unsettled areas of the north and east, and the army response to the unrest was more restrained in 1992. An inspector general of government (IGG) was appointed to serve as a "watchdog" on government but the incumbent's effectiveness was undermined by the IGG's large caseload and the fact that the inspector general served at the president's pleasure.

The government declared northern Uganda "pacified" in late 1991, following a three-month-long army sweep that included house-to-house searches in Gulu, Lira, Kitgum, and Apac districts. Residents were asked to produce poll tax receipts and other documents to prove their identity. In some cases, civilians were assaulted, and a few were executed for failing to comply.

Museveni also attempted to bring order to Uganda's foreign relations. He met in Nairobi with Kenyan president Daniel T. arap Moi and Tanzanian president Ali Hassan Mwinyi in late 1991, and they agreed to develop closer ties among the three countries. Relations with Kenya had been strained, primarily because of continuing clashes along their common border. Most of the attacks were provoked by banditry and cross-border skirmishes among isolated groups of soldiers or herders, but the two leaders harbored mutual suspicions of one another. Moi feared Museveni's close ties with Libyan leader Muammar Qadhafi could contribute to destabilization in Kenya, where ethnic and political tensions were already high. (This fear probably diminished, however, following Libya's June 1992 termination of its military relationship with Uganda.) The three leaders agreed to coordinate policies in security, trade, transportation, agriculture, and industry, and to pursue other avenues for regional cooperation.

Relations with Rwanda remained strained as of mid-1992. Fighting continued along the Uganda-Rwanda border following the October 1990 invasion of Rwanda by Rwandan exiles in Uganda. Many members of the invading rebel army, the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), had been members of the Ugandan Army. Rwandan president JuvÉnal Habyarimana continued to accuse Museveni of allowing, and even supporting, RPF operations from Ugandan territory, and Rwandan forces struck back across the border several times in 1991 and early 1992. Ugandan officials estimated that several thousand Ugandans had been killed, and more than 30,000 displaced, by the conflict. Representatives of the Organization of African Unity (OAU), along with officials from Rwanda, Burundi, Tanzania, and Zaire, met several times in 1991 and 1992 and urged the warring parties to observe the ceasefire agreed to in March 1991, but fighting continued as of mid-1992.

Unrest in Zaire arising out of economic deterioration and a stalemate over political reform also contributed to the security crisis in southwestern Uganda in 1992. Ugandan officials claimed more than 20,000 Zairian refugees had entered Uganda, seeking refuge from marauding Zairian troops and antigovernment rebel banditry.

In northern Uganda, similar problems arose out of civil war and drought conditions in Sudan. In 1991 and 1992, Sudanese army assaults on antigovernment rebel units near the Ugandan border were forcing southern Sudanese to seek refuge in the increasingly drought-stricken area of northern Uganda, and in a few cases Sudanese attacks extended into Ugandan territory.

The influx of refugees strained an already struggling Ugandan economy. Uganda's overall economic growth continued in 1992, but fell from the impressive rate of nearly 6 percent in 1990 and almost 5 percent in 1991 to a projected 4.5 percent in 1992. The government attributed the positive performance to the nation's returning political stability and an increasingly favorable investment environment. Foreign assistance also continued to play a significant role in economic growth. Inflation fell from triple-digit levels to about 25 percent in 1990 but rose to 38 percent in 1991. Targeted inflation for 1992 was 15 percent.

The fiscal year 1992 budget included total government spending of 674.35 billion Uganda shillings (USh), or about US$911.3 million, of which the government claimed defense spending would constitute about 20 percent. Educational expenditures would constitute 12 percent; health care, 6.5 percent; 3 percent was earmarked for providing safe drinking water. Roughly one-third of expenditures were to be financed by government revenues; one- third by foreign grants; and one-third by borrowing, debt rescheduling, and the sale of treasury bills.

Agricultural growth reached 2.8 percent in 1991 and was expected to exceed that in 1992. Cotton production doubled in 1991 over 1990 levels; production of tea and tobacco also increased. Coffee earnings fell to about US$140 million in 1991-- largely the result of the collapse of the International Coffee Agreement, which had regulated world market prices--but coffee still accounted for about 70 percent of merchandise export earnings. Nontraditional export earnings, although small in comparison with traditional exports, doubled between 1990 and 1992 to more than US$50 million, largely because of government support programs that included low-interest loans and expanded credit opportunities to encourage the production of a wider variety of agricultural products.

Nevertheless, Uganda's trade deficit remained high in 1991, with imports roughly three times the value of exports. Combined with high interest payments, the unfavorable trade deficit produced a current account deficit of almost US$500 million. Debt service requirements reached roughly 75 percent of export earnings, with arrears mounting steadily. Most of Uganda's external debt was owed to multilateral creditors and therefore could not be rescheduled.

The government continued to implement features of the 1987-91 economic rehabilitation program, such as liberalizing the marketing of agricultural produce. In 1992 a few coffee producers' groups were handling coffee marketing, although the government's Coffee Marketing Board remained active. In early 1992, the government introduced an auction system for allocating foreign exchange on the basis of market dictates rather than government selection among importers. To help improve Uganda's investment climate, the government also began restoring to its original owners the property that had been expropriated during the 1970s, and negotiating compensation in a few other cases.

The government announced that it would privatize, at least in part, 100 of the country's 116 public enterprises and eliminate 16 parastatals. It would retain majority shares in commercial banking; copper mining; housing; airlines; breweries; grain milling; pharmaceutical distribution; steel and cement production; textile and sugar manufacturing; and the marketing of coffee, cotton, and most agricultural produce. Private investors, including foreigners, would be able to purchase shares in companies in which the government was a major shareholder. The government planned to retain full ownership of electric utilities, railroads, air cargo services, development finance banking, posts and telecommunications, insurance agencies, tourist agencies, and newspaper publishing. To improve accountability among these enterprises, it intended to reduce the number of political appointments and increase its oversight of recordkeeping practices.

Civil service reform was also an important goal for the early 1990s. With the elimination of "ghost" employees from government rolls in mid-1991, the number of public employees outside the education sector was reduced from 90,000 to roughly 64,000, and teachers' rolls were reduced to roughly 80,000. The salaries of remaining government employees were increased, some by as much as 40 percent, after these payroll cuts were announced.

Despite significant progress and ambitious planning, Uganda faced serious economic and political problems in 1992. Lingering insurgency campaigns in the north and east, increased defense spending, and serious military abuses reinforced one another to erode public confidence. The government's commitment to economic development provided hope of improved living standards, but the combined economic and security problems, along with the effects of two decades of neglect of education and social services, led many people to question whether Museveni could deliver on his pledge to restore broad-based democracy to Uganda.

June 15, 1992

Rita M. Byrnes

Chapter 1. Historical Setting

![[GIF]](baobab2.jpg) |

The baobab tree, ancient symbol of the African plains

UGANDA WAS ONE of the lesser-known African countries until the 1970s when Idi Amin Dada rose to the presidency. His bizarre public pronouncements--ranging from gratuitous advice for Richard Nixon to his proclaimed intent to raise a monument to Adolf Hitler--fascinated the popular news media. Beneath the facade of buffoonery, however, the darker reality of massacres and disappearances was considered equally newsworthy. Uganda became known as an African horror story, fully identified with its field marshal president. Even a decade after Amin's flight from Uganda in 1979, popular imagination still insisted on linking the country and its exiled former ruler.

But Amin's well-publicized excesses at the expense of Uganda and its citizens were not unique, nor were they the earliest assaults on the rule of law. They were foreshadowed by Amin's predecessor, Apolo Milton Obote, who suspended the 1962 constitution and ruled part of Uganda by martial law for five years before a military coup in 1971 brought Amin into power. Amin's bloody regime was followed by an even bloodier one-- Obote's second term as president during the civil war from 1981 to 1985, when government troops carried out genocidal sweeps of the rural populace in a region that became known as the Luwero Triangle. The dramatic collapse of coherent government under Amin and his plunder of his nation's economy, followed by the even greater failure of the second Obote government in the 1980s, raised the essential question--"what went wrong?"

At Uganda's independence in October 1962 there was little indication that the country was headed for disaster. On the contrary, it appeared a model of stability and potential progress. Unlike neighboring Kenya, Uganda had no alien white settler class attempting to monopolize the rewards of the cashcrop economy. Nor was there any recent legacy of bitter and violent conflict in Uganda to compare with the 1950s Mau Mau rebellion in Kenya. In Uganda it was African producers who grew the cotton and coffee that brought a higher standard of living, financed the education of their children, and led to increased expectations for the future.

Unlike neighboring Tanzania, Uganda enjoyed rich natural resources, a flourishing economy, and an impressive number of educated and prosperous middle-class African professionals, including business people, doctors, lawyers, and scientists. And unlike neighboring Zaire (the former Belgian Congo), which experienced only a brief period of independence before descending into chaos and misrule, Uganda's first few years of self-rule saw a series of successful development projects. The new government built many new schools, modernized the transportation network, and increased manufacturing output as well as national income. With its prestigious national Makerere University, its gleaming new teaching hospital at Mulago, its Owen Falls hydroelectric project at Jinja--all gifts of the departing British--Uganda at independence looked optimistically to the future.

Independence, too, was in a sense a gift of the British because it came without a struggle. The British determined a timetable for withdrawal before local groups had organized an effective nationalist movement. Uganda's political parties emerged in response to impending independence rather than as a means of winning it.

In part the result of its fairly smooth transition to independence, the near absence of nationalism among Uganda's diverse ethnic groups led to a series of political compromises. The first was a government made up of coalitions of local and regional interest groups loosely organized into political parties. The national government was presided over by a prime minister whose principal role appeared to be that of a broker, trading patronage and development projects--such as roads, schools, and dispensaries--to local or regional interest groups in return for political support. It was not the strong, directive, ideologically clothed central government desired by most African political leaders, but it worked. And it might reasonably have been expected to continue to work, because there were exchanges and payoffs at all levels and to all regions.

As Uganda's first prime minister, Obote displayed a talent for acting as a broker for groups divided from each other by distance, language, cultural tradition, historical enmities, and rivalries in the form of competing religions--Islam, Roman Catholicism, and Protestantism.

Observers with a powerfully developed sense of hindsight could point to a series of divisions within Ugandan society that contributed to its eventual national disintegration. First, the language gulf between the Nilotic-speaking people of the north and the Bantu-speaking peoples of the south was as wide as that between speakers of Slavic and of Romance languages in Europe. Second, there was an economic divide between the pastoralists, who occupied the drier rangelands of the west and north, and the agriculturists, who cultivated the better-watered highland or lakeside regions. Third, there was a long-standing division between the centralized and sometimes despotic rule of the ancient African kingdoms and the kinship-based politics of recent times, which were characterized by a greater sense of equality and participation. Furthermore, there was a historical political division among the kingdoms themselves. They were often at odds-- as in the case of Buganda and Bunyoro and between other precolonial polities that disputed control of particular lands. There also were the historical complaints of particular religious groups that had lost ground to rivals in the past: for example, the eclipse of the Muslims at the end of the nineteenth century by Christians allied to British colonialism created an enduring grievance. In addition, Bunyoro's nineteenth-century losses of territory to an expanding Buganda kingdom, allied to British imperialism, gave rise to a problem that would emerge after independence as the "lost counties" issue. Another divisive factor was the uneven development in the colonial period, whereby the south secured railroad transport, cash crops, mission education, and the seat of government, seemingly at the expense of other regions which were still trying to catch up after independence. Another factor was conflicting local nationalism (often misleadingly termed "tribalism"), the most conspicuous example of which was Buganda, whose population of over one million, extensive territory in the favored south of Uganda, and self-proclaimed superiority created a serious backlash among other peoples. Nubians had been brought in from Sudan to serve as a colonial coercive force to suppress local tax revolts. This community shared little sense of identification with Uganda. The presence of an alien community of professional military people clustered around military encampments added fuel to the fire. And there was another alien community that dominated commercial life in the cities and towns--Asians who had arrived with British colonial rule. Finally, the closely related peoples of nearby Zaire and Sudan soon became embroiled in their own civil wars during the colonial period, drawing in ethnically related Ugandans.

This formidable list of obstacles to national integration, coupled with the absence of nationalist sentiment, left the newly independent Uganda vulnerable to political instability in the 1960s. It was by no means inevitable that the government by consensus and compromise characterizing the early 1960s would devolve into the military near-anarchy of the 1970s. The conditions contributing to such a debacle, however, were already present at independence.

![[JPEG]](ug01_02a.jpg) |

Drawing of the royal capital of Buganda at the time of journalist Henry M. Stanley's visit in 1875

|

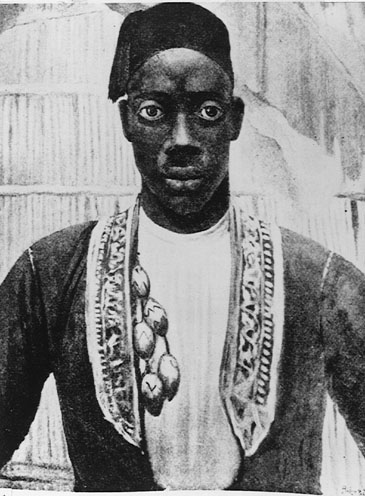

Kabaka Mutesa I, who reigned from 1856 to 1884

Uganda's strategic position along the central African Rift Valley, its favorable climate at an altitude of 1,200 meters and above, and the reliable rainfall around the Lake Victoria Basin made it attractive to African cultivators and herders as early as the fourth century B.C. Core samples from the bottom of Lake Victoria have revealed that dense rainforest once covered the land around the lake. Centuries of cultivation removed almost all the original tree cover.

The cultivators who gradually cleared the forest were probably Bantu-speaking people, whose slow but inexorable expansion gradually populated most of Africa south of the Sahara Desert. Their knowledge of agriculture and use of iron technology permitted them to clear the land and feed ever larger numbers of settlers. They displaced small bands of indigenous huntergatherers , who relocated to the less accessible mountains. Meanwhile, by the fourth century B.C., the Bantu-speaking metallurgists were perfecting iron smelting to produce mediumgrade carbon steel in preheated forced draft furnaces--a technique not achieved in Europe until the Siemens process of the nineteenth century. Although most of these developments were taking place southwest of modern Ugandan boundaries, iron was mined and smelted in many parts of the country not long afterward.

As the Bantu-speaking agriculturists multiplied over the centuries, they evolved a form of government by clan (see Glossary) chiefs. This kinship-organized system was useful for coordinating work projects, settling internal disputes, and carrying out religious observances to clan deities, but it could effectively govern only a limited number of people. Larger polities began to form states by the end of the first millennium A.D., some of which would ultimately govern over a million subjects each.

The stimulus to the formation of states may have been the meeting of people of differing cultures. The lake shores became densely settled by Bantu speakers, particularly after the introduction of the banana, or plantain, as a basic food crop around A.D. 1000; farther north in the short grass uplands, where rainfall was intermittent, pastoralists were moving south from the area of the Nile River in search of better pastures. Indeed, a short grass "corridor" existed north and west of Lake Victoria through which successive waves of herders may have passed on the way to central and southern Africa. The meeting of these peoples resulted in trade across various ecological zones and evolved into more permanent relationships.

Nilotic-speaking pastoralists were mobile and ready to resort to arms in defense of their own cattle or raids to appropriate the cattle of others. But their political organization was minimal, based on kinship and decision making by kin-group elders. In the meeting of cultures, they may have acquired the ideas and symbols of political chiefship from the Bantu-speakers, to whom they could offer military protection. A system of patronclient relationships developed, whereby a pastoral elite emerged, entrusting the care of cattle to subjects who used the manure to improve the fertility of their increasingly overworked gardens and fields. The earliest of these states may have been established in the fifteenth century by a group of pastoral rulers called the Chwezi. Although legends depicted the Chwezi as supernatural beings, their material remains at the archaeological sites of Bigo and Mubende have shown that they were human and the probable ancestors of the modern Hima or Tutsi (Watutsi) pastoralists of Rwanda and Burundi. During the fifteenth century, the Chwezi were displaced by a new Nilotic-speaking pastoral group called the Bito. The Chwezi appear to have moved south of present-day Uganda to establish kingdoms in northwest Tanzania, Rwanda, and Burundi.

From this process of cultural contact and state formation, three different types of states emerged. The Hima type was later to be seen in Rwanda and Burundi. It preserved a caste system whereby the rulers and their pastoral relatives attempted to maintain strict separation from the agricultural subjects, called Hutu. The Hima rulers lost their Nilotic language and became Bantu speakers, but they preserved an ideology of superiority in political and social life and attempted to monopolize high status and wealth. In the twentieth century, the Hutu revolt after independence led to the expulsion from Rwanda of the Hima elite, who became refugees in Uganda. A counterrevolution in Burundi secured power for the Hima through periodic massacres of the Hutu majority.

The Bito type of state, in contrast with that of the Hima, was established in Bunyoro, which for several centuries was the dominant political power in the region. Bito immigrants displaced the influential Hima and secured power for themselves as a royal clan, ruling over Hima pastoralists and Hutu agriculturalists alike. No rigid caste lines divided Bito society. The weakness of the Bito ideology was that, in theory, it granted every Bito clan member royal status and with it the eligibility to rule. Although some of these ambitions might be fulfilled by the Bunyoro king's (omukama) granting his kin offices as governors of districts, there was always the danger of coup d'État or secession by overambitious relatives. Thus, in Bunyoro, periods of political stability and expansion were interrupted by civil wars and secessions.

The third type of state to emerge in Uganda was that of Buganda, on the northern shores of Lake Victoria. This area of swamp and hillside was not attractive to the rulers of pastoral states farther north and west. It became a refuge area, however, for those who wished to escape rule by Bunyoro or for factions within Bunyoro who were defeated in contests for power. One such group from Bunyoro, headed by Prince Kimera, arrived in Buganda early in the fifteenth century. Assimilation of refugee elements had already strained the ruling abilities of Buganda's various clan chiefs and a supraclan political organization was already emerging. Kimera seized the initiative in this trend and became the first effective king (kabaka) of the fledgling Buganda state. Ganda oral traditions later sought to disguise this intrusion from Bunyoro by claiming earlier, shadowy, quasisupernatural kabakas.

Unlike the Hima caste system or the Bunyoro royal clan political monopoly, Buganda's kingship was made a kind of state lottery in which all clans could participate. Each new king was identified with the clan of his mother, rather than that of his father. All clans readily provided wives to the ruling kabaka, who had eligible sons by most of them. When the ruler died, his successor was chosen by clan elders from among the eligible princes, each of whom belonged to the clan of his mother. In this way, the throne was never the property of a single clan for more than one reign.

Consolidating their efforts behind a centralized kingship, the Baganda (people of Buganda; sing., Muganda) shifted away from defensive strategies and toward expansion. By the mid-nineteenth century, Buganda had doubled and redoubled its territory. Newly conquered lands were placed under chiefs nominated by the king. Buganda's armies and the royal tax collectors traveled swiftly to all parts of the kingdom along specially constructed roads which crossed streams and swamps by bridges and viaducts. On Lake Victoria (which the Baganda called Nnalubale), a royal navy of outrigger canoes, commanded by an admiral who was chief of the Lungfish clan, could transport Baganda commandos to raid any shore of the lake. The journalist Henry M. Stanley visited Buganda in 1875 and provided an estimate of Buganda troop strength. Stanley counted 125,000 troops marching off on a single campaign to the east, where a fleet of 230 war canoes waited to act as auxiliary naval support.

At Buganda's capital, Stanley found a well-ordered town of about 40,000 surrounding the king's palace, which was situated atop a commanding hill. A wall more than four kilometers in circumference surrounded the palace compound, which was filled with grass-roofed houses, meeting halls, and storage buildings. At the entrance to the court burned the royal fire (gombolola), which would only be extinguished when the kabaka died. Thronging the grounds were foreign ambassadors seeking audiences, chiefs going to the royal advisory council, messengers running errands, and a corps of young pages, who served the kabaka while training to become future chiefs. For communication across the kingdom, the messengers were supplemented by drum signals.

Most communities in Uganda, however, were not organized on such a vast political scale. To the north, the Nilotic-speaking Acholi people adopted some of the ideas and regalia of kingship from Bunyoro in the eighteenth century. Chiefs (rwots) acquired royal drums, collected tribute from followers, and redistributed it to those who were most loyal. The mobilization of larger numbers of subjects permitted successful hunts for meat. Extensive areas of bushland were surrounded by beaters, who forced the game to a central killing point in a hunting technique that was still practiced in areas of central Africa in 1989. But these Acholi chieftaincies remained relatively small in size, and within them the power of the clans remained strong enough to challenge that of the rwot.

Until the middle of the nineteenth century, Uganda remained relatively isolated from the outside world. The central African lake region was, after all, a world in miniature, with an internal trade system, a great power rivalry between Buganda and Bunyoro, and its own inland seas. When intrusion from the outside world finally came, it was in the form of long-distance trade for ivory.

Ivory had been a staple trade item from the East Africa coast since before the time of Christ. But growing world demand in the nineteenth century, together with the provision of increasingly efficient firearms to hunters, created a moving "ivory frontier" as elephant herds near the coast were nearly exterminated. Leading large caravans financed by Indian moneylenders, coastal Arab traders based on Zanzibar (united with Tanganyika in 1964 to form Tanzania) had reached Lake Victoria by 1844. One trader, Ahmad bin Ibrahim, introduced Buganda's kabaka to the advantages of foreign trade: the acquisition of imported cloth and, more important, guns and gunpowder. Ibrahim also introduced the religion of Islam, but the kabaka was more interested in guns. By the 1860s, Buganda was the destination of ever more caravans, and the kabaka and his chiefs began to dress in cloth called mericani, which was woven in Massachusetts and carried to Zanzibar by American traders. It was judged finer in quality than European or Indian cloth, and increasing numbers of ivory tusks were collected to pay for it. Bunyoro sought to attract foreign trade as well, in an effort to keep up with Buganda in the burgeoning arms race.

Bunyoro also found itself threatened from the north by Egyptian-sponsored agents who sought ivory and slaves but who, unlike the Arab traders from Zanzibar, were also promoting foreign conquest. Khedive Ismael of Egypt aspired to build an empire on the Upper Nile; by the 1870s, his motley band of ivory traders and slave raiders had reached the frontiers of Bunyoro. The khedive sent a British explorer, Samuel Baker, to raise the Egyptian flag over Bunyoro. The Banyoro (people of Bunyoro) resisted this attempt, and Baker had to fight a desperate battle to secure his retreat. Baker regarded the resistance as an act of treachery, and he denounced the Banyoro in a book that was widely read in Britain. Later British empire builders arrived in Uganda with a predisposition against Bunyoro, which eventually would cost the kingdom half its territory until the "lost counties" were restored to Bunyoro after independence.

Farther north the Acholi responded more favorably to the Egyptian demand for ivory. They were already famous hunters and quickly acquired guns in return for tusks. The guns permitted the Acholi to retain their independence but altered the balance of power within Acholi territory, which for the first time experienced unequal distribution of wealth based on control of firearms.

Meanwhile, Buganda was receiving not only trade goods and guns, but a stream of foreign visitors as well. The explorer J.H. Speke passed through Buganda in 1862 and claimed he had discovered the source of the Nile. Both Speke and Stanley (based on his 1875 stay in Uganda) wrote books that praised the Baganda for their organizational skills and willingness to modernize. Stanley went further and attempted to convert the king to Christianity. Finding Kabaka Mutesa I apparently receptive, Stanley wrote to the Church Missionary Society (CMS) in London and persuaded it to send missionaries to Buganda in 1877. Two years after the CMS established a mission, French Catholic White Fathers also arrived at the king's court, and the stage was set for a fierce religious and nationalist rivalry in which Zanzibarbased Muslim traders also participated. By the mid-1880s, all three parties had been successful in converting substantial numbers of Baganda, some of whom attained important positions at court. When a new young kabaka, Mwanga, attempted to halt the dangerous foreign ideologies that he saw threatening the state, he was deposed by the armed converts in 1888. A four-year civil war ensued in which the Muslims were initially successful and proclaimed an Islamic state. They were soon defeated, however, and were not able to renew their effort.

The victorious Protestant and Catholic converts then divided the Buganda kingdom, which they ruled through a figurehead kabaka dependent on their guns and goodwill. Thus, outside religion had disrupted and transformed the traditional state. Soon afterwards, the arrival of competing European imperialists-- the German Doctor Karl Peters (an erstwhile philosophy professor) and the British Captain Frederick Lugard--broke the Christian alliance; the British Protestant missionaries urged acceptance of the British flag, while the French Catholic mission either supported the Germans (in the absence of French imperialists) or called for Buganda to retain its independence. In January 1892, fighting broke out between the Protestant and Catholic Baganda converts. The Catholics quickly gained the upper hand, until Lugard intervened with a prototype machine gun, the Maxim (named after its American inventor, Hiram Maxim). The Maxim decided the issue in favor of the pro-British Protestants; the French Catholic mission was burned to the ground, and the French bishop fled. The resultant scandal was settled in Europe when the British government paid compensation to the French mission and persuaded the Germans to relinquish their claim to Uganda.

With Buganda secured by Lugard and the Germans no longer contending for control, the British began to enlarge their claim to the "headwaters of the Nile," as they called the land north of Lake Victoria. Allying with the Protestant Baganda chiefs, the British set about conquering the rest of the country, aided by Nubian mercenary troops who had formerly served the khedive of Egypt. Bunyoro had been spared the religious civil wars of Buganda and was firmly united by its king, Kabarega, who had several regiments of troops armed with guns. After five years of bloody conflict, the British occupied Bunyoro and conquered Acholi and the northern region, and the rough outlines of the Uganda Protectorate came into being. Other African polities, such as the Ankole kingdom to the southwest, signed treaties with the British, as did the chiefdoms of Busoga, but the kinship-based peoples of eastern and northeastern Uganda had to be overcome by military force.

A mutiny by Nubian mercenary troops in 1897 was only barely suppressed after two years of fighting, during which Baganda Christian allies of the British once again demonstrated their support for the colonial power. As a reward for this support, and in recognition of Buganda's formidable military presence, the British negotiated a separate treaty with Buganda, granting it a large measure of autonomy and self-government within the larger protectorate under indirect rule. One-half of Bunyoro's conquered territory was awarded to Buganda as well, including the historic heartland of the kingdom containing several Nyoro (Bunyoro) royal tombs. Buganda doubled in size from ten to twenty counties (sazas), but the "lost counties" of Bunyoro remained a continuing grievance that would return to haunt Buganda in the 1960s.

![[JPEG]](ug01_03a.jpg) |

Kabaka Mutesa I, who reigned from 1856 to 1884

Although momentous change occurred during the colonial era in Uganda, some characteristics of late-nineteenth century African society survived to reemerge at the time of independence. Colonial rule affected local economic systems dramatically, in part because the first concern of the British was financial. Quelling the 1897 mutiny had been costly--units of the Indian army had been transported to Uganda at considerable expense. The new commissioner of Uganda in 1900, Sir Harry H. Johnston, had orders to establish an efficient administration and to levy taxes as quickly as possible. Johnston approached the chiefs in Buganda with offers of jobs in the colonial administration in return for their collaboration. The chiefs, whom Johnston characterized in demeaning terms, were more interested in preserving Buganda as a self-governing entity, continuing the royal line of kabakas, and securing private land tenure for themselves and their supporters. Hard bargaining ensued, but the chiefs ended up with everything they wanted, including one-half of all the land in Buganda. The half left to the British as "Crown Land" was later found to be largely swamp and scrub.

Johnston's Buganda Agreement of 1900 imposed a tax on huts and guns, designated the chiefs as tax collectors, and testified to the continued alliance of British and Baganda interests. The British signed much less generous treaties with the other kingdoms (Toro in 1900, Ankole in 1901, and Bunyoro in 1933) without the provision of large-scale private land tenure. The smaller chiefdoms of Busoga were ignored.

The Baganda immediately offered their services to the British as administrators over their recently conquered neighbors, an offer which was attractive to the economy-minded colonial administration. Baganda agents fanned out as local tax collectors and labor organizers in areas such as Kigezi, Mbale, and, significantly, Bunyoro. This subimperialism and Ganda cultural chauvinism were resented by the people being administered. Wherever they went, Baganda insisted on the exclusive use of their language, Luganda, and they planted bananas as the only proper food worth eating. They regarded their traditional dress-- long cotton gowns called kanzus--as civilized; all else was barbarian. They also encouraged and engaged in mission work, attempting to convert locals to their form of Christianity or Islam. In some areas, the resulting backlash aided the efforts of religious rivals--for example, Catholics won converts in areas where oppressive rule was identified with a Protestant Muganda chief.

The people of Bunyoro were particularly aggrieved, having fought the Baganda and the British; having a substantial section of their heartland annexed to Buganda as the "lost counties;" and finally having "arrogant" Baganda administrators issuing orders, collecting taxes, and forcing unpaid labor. In 1907 the Banyoro rose in a rebellion called nyangire, or "refusing," and succeeded in having the Baganda subimperial agents withdrawn.

Meanwhile, in 1901 the completion of the Uganda railroad from the coast at Mombasa to the Lake Victoria port of Kisumu moved colonial authorities to encourage the growth of cash crops to help pay the railroad's operating costs. Another result of the railroad construction was the 1902 decision to transfer the eastern section of the Uganda Protectorate to the Kenya Colony, then called the East African Protectorate, to keep the entire railroad line under one local colonial administration. Because the railroad experienced cost overruns in Kenya, the British decided to justify its exceptional expense and pay its operating costs by introducing large-scale European settlement in a vast tract of land that became a center of cash-crop agriculture known as the "white highlands."

In many areas of Uganda, by contrast, agricultural production was placed in the hands of Africans, if they responded to the opportunity. Cotton was the crop of choice, largely because of pressure by the British Cotton Growing Association, textile manufacturers who urged the colonies to provide raw materials for British mills. Even the CMS joined the effort by launching the Uganda Company (managed by a former missionary) to promote cotton planting and to buy and transport the produce.

Buganda, with its strategic location on the lakeside, reaped the benefits of cotton growing. The advantages of this crop were quickly recognized by the Baganda chiefs who had newly acquired freehold estates, which came to be known as mailo land because they were measured in square miles. In 1905 the initial baled cotton export was valued at £200; in 1906, £1,000; in 1907; £11,000; and in 1908, £52,000. By 1915 the value of cotton exports had climbed to £369,000, and Britain was able to end its subsidy of colonial administration in Uganda, while in Kenya the white settlers required continuing subsidies by the home government.

The income generated by cotton sales made the Buganda kingdom relatively prosperous, compared with the rest of colonial Uganda, although before World War I cotton was also being grown in the eastern regions of Busoga, Lango, and Teso. Many Baganda spent their new earnings on imported clothing, bicycles, metal roofing, and even automobiles. They also invested in their children's educations. The Christian missions emphasized literacy skills, and African converts quickly learned to read and write. By 1911 two popular journals, Ebifa (News) and Munno (Your Friend), were published monthly in Luganda. Heavily supported by African funds, new schools were soon turning out graduating classes at Mengo High School, St. Mary's Kisubi, Namilyango, Gayaza, and King's College Budo--all in Buganda. The chief minister of the Buganda kingdom, Sir Apolo Kagwa, personally awarded a bicycle to the top graduate at King's College Budo, together with the promise of a government job. The schools, in fact, had inherited the educational function formerly performed in the kabaka's palace, where generations of young pages had been trained to become chiefs. Now the qualifications sought were literacy and skills, including typing and English translation.

Two important principles of precolonial political life carried over into the colonial era: clientage, whereby ambitious younger officeholders attached themselves to older high-ranking chiefs, and generational conflict, which resulted when the younger generation sought to expel their elders from office in order to replace them. After World War I, the younger aspirants to high office in Buganda became impatient with the seemingly perpetual tenure of Sir Apolo and his contemporaries, who lacked many of the skills that members of the younger generation had acquired through schooling. Calling themselves the Young Baganda Association, members of the new generation attached themselves to the young kabaka, Daudi Chwa, who was the figurehead ruler of Buganda under indirect rule. But Kabaka Daudi never gained real political power, and after a short and frustrating reign, he died at the relatively young age of forty-three.

Far more promising as a source of political support were the British colonial officers, who welcomed the typing and translation skills of school graduates and advanced the careers of their favorites. The contest was decided after World War I, when an influx of British ex-military officers, now serving as district commissioners, began to feel that self-government was an obstacle to good government. Specifically, they accused Sir Apolo and his generation of inefficiency, abuse of power, and failure to keep adequate financial accounts--charges that were not hard to document. Sir Apolo resigned in 1926, at about the same time that a host of elderly Baganda chiefs were replaced by a new generation of officeholders. The Buganda treasury was also audited that year for the first time. Although it was not a nationalist organization, the Young Baganda Association claimed to represent popular African dissatisfaction with the old order. As soon as the younger Baganda had replaced the older generation in office, however, their objections to privilege accompanying power ceased. The pattern persisted in Ugandan politics up to and after independence.

The commoners, who had been laboring on the cotton estates of the chiefs before World War I, did not remain servile. As time passed, they bought small parcels of land from their erstwhile landlords. This land fragmentation was aided by the British, who in 1927 forced the chiefs to limit severely the rents and obligatory labor they could demand from their tenants. Thus the oligarchy of landed chiefs who had emerged with the Buganda Agreement of 1900 declined in importance, and agricultural production shifted to independent smallholders, who grew cotton, and later coffee, for the export market.

Unlike Tanganyika, which was devastated during the prolonged fighting between Britain and Germany in the East African campaign of World War I, Uganda prospered from wartime agricultural production. After the population losses during the era of conquest and the losses to disease at the turn of the century (particularly the devastating sleeping sickness epidemic of 1900- 1906), Uganda's population was growing again. Even the 1930s depression seemed to affect smallholder cash farmers in Uganda less severely than it did the white settler producers in Kenya. Ugandans simply grew their own food until rising prices made export crops attractive again.

Two issues continued to create grievance through the 1930s and 1940s. The colonial government strictly regulated the buying and processing of cash crops, setting prices and reserving the role of intermediary for Asians, who were thought to be more efficient. The British and Asians firmly repelled African attempts to break into cotton ginning. In addition, on the Asian- owned sugar plantations established in the 1920s, labor for sugarcane and other cash crops was increasingly provided by migrants from peripheral areas of Uganda and even from outside Uganda.

In 1949 discontented Baganda rioted and burned down the houses of progovernment chiefs. The rioters had three demands: the right to bypass government price controls on the export sales of cotton, the removal of the Asian monopoly over cotton ginning, and the right to have their own representatives in local government replace chiefs appointed by the British. They were critical as well of the young kabaka, Frederick Walugembe Mutesa II (also known as Kabaka Freddie), for his inattention to the needs of his people. The British governor, Sir John Hall, regarded the riots as the work of communist-inspired agitators and rejected the suggested reforms.

Far from leading the people into confrontation, Uganda's would-be agitators were slow to respond to popular discontent. Nevertheless, the Uganda African Farmers Union, founded by I.K. Musazi in 1947, was blamed for the riots and was banned by the British. Musazi's Uganda National Congress replaced the farmers union in 1952, but because the congress remained a casual discussion group more than an organized political party, it stagnated and came to an end just two years after its inception.

Meanwhile, the British began to move ahead of the Ugandans in preparing for independence. The effects of Britain's postwar withdrawal from India, the march of nationalism in West Africa, and a more liberal philosophy in the Colonial Office geared toward future self-rule all began to be felt in Uganda. The embodiment of these issues arrived in 1952 in the person of a new and energetic reformist governor, Sir Andrew Cohen (formerly undersecretary for African affairs in the Colonial Office). Cohen set about preparing Uganda for independence. On the economic side, he removed obstacles to African cotton ginning, rescinded price discrimination against African-grown coffee, encouraged cooperatives, and established the Uganda Development Corporation to promote and finance new projects. On the political side, he reorganized the Legislative Council, which had consisted of an unrepresentative selection of interest groups heavily favoring the European community, to include African representatives elected from districts throughout Uganda. This system became a prototype for the future parliament.

The prospect of elections caused a sudden proliferation of new political parties. This development alarmed the old-guard leaders within the Uganda kingdoms, because they realized that the center of power would be at the national level. The spark that ignited wider opposition to Governor Cohen's reforms was a 1953 speech in London in which the secretary of state for colonies referred to the possibility of a federation of the three East African territories (Kenya, Uganda, and Tanganyika), similar to that established in central Africa. Many Ugandans were aware of the Central African Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland (later Zimbabwe, Zambia, and Malawi) and its domination by white settler interests. Ugandans deeply feared the prospect of an East African federation dominated by the racist settlers of Kenya, which was then in the midst of the bitter Mau Mau uprising. They had vigorously resisted a similar suggestion by the 1930 Hilton Young Commission. Confidence in Cohen vanished just as the governor was preparing to urge Buganda to recognize that its special status would have to be sacrificed in the interests of a new and larger nation-state.

Kabaka Freddie, who had been regarded by his subjects as uninterested in their welfare, now refused to cooperate with Cohen's plan for an integrated Buganda. Instead, he demanded that Buganda be separated from the rest of the protectorate and transferred to Foreign Office jurisdiction. Cohen's response to this crisis was to deport the kabaka to a comfortable exile in London. His forced departure made the kabaka an instant martyr in the eyes of the Baganda, whose latent separatism and anticolonial sentiments set off a storm of protest. Cohen's action had backfired, and he could find no one among the Baganda prepared or able to mobilize support for his schemes. After two frustrating years of unrelenting Ganda hostility and obstruction, Cohen was forced to reinstate Kabaka Freddie.

The negotiations leading to the kabaka's return had an outcome similar to the negotiations of Commissioner Johnston in 1900; although appearing to satisfy the British, they were a resounding victory for the Baganda. Cohen secured the kabaka's agreement not to oppose independence within the larger Uganda framework. Not only was the kabaka reinstated in return, but for the first time since 1889, the monarch was given the power to appoint and dismiss his chiefs (Buganda government officials) instead of acting as a mere figurehead while they conducted the affairs of government. The kabaka's new power was cloaked in the misleading claim that he would be only a "constitutional monarch," while in fact he was a leading player in deciding how Uganda would be governed. A new grouping of Baganda calling themselves "the King's Friends" rallied to the kabaka's defense. They were conservative, fiercely loyal to Buganda as a kingdom, and willing to entertain the prospect of participation in an independent Uganda only if it were headed by the kabaka. Baganda politicians who did not share this vision or who were opposed to the "King's Friends" found themselves branded as the "King's Enemies," which meant political and social ostracism.

The major exception to this rule were the Roman Catholic Baganda who had formed their own party, the Democratic Party (DP), led by Benedicto Kiwanuka. Many Catholics had felt excluded from the Protestant-dominated establishment in Buganda ever since Lugard's Maxim had turned the tide in 1892. The kabaka had to be Protestant, and he was invested in a coronation ceremony modeled on that of British monarchs (who are invested by the Church of England's Archbishop of Canterbury) that took place at the main Protestant church. Religion and politics were equally inseparable in the other kingdoms throughout Uganda. The DP had Catholic as well as other adherents and was probably the best organized of all the parties preparing for elections. It had printing presses and the backing of the popular newspaper, Munno, which was published at the St. Mary's Kisubi mission.

Elsewhere in Uganda, the emergence of the kabaka as a political force provoked immediate hostility. Political parties and local interest groups were riddled with divisions and rivalries, but they shared one concern: they were determined not to be dominated by Buganda. In 1960 a political organizer from Lango, Milton Obote, seized the initiative and formed a new party, the Uganda People's Congress (UPC), as a coalition of all those outside the Roman Catholic-dominated DP who opposed Buganda hegemony.

The steps Cohen had initiated to bring about the independence of a unified Uganda state had led to a polarization between factions from Buganda and those opposed to its domination. Buganda's population in 1959 was 2 million, out of Uganda's total of 6 million. Even discounting the many non-Baganda resident in Buganda, there were at least 1 million people who owed allegiance to the kabaka--too many to be overlooked or shunted aside, but too few to dominate the country as a whole. At the London Conference of 1960, it was obvious that Buganda autonomy and a strong unitary government were incompatible, but no compromise emerged, and the decision on the form of government was postponed. The British announced that elections would be held in March 1961 for "responsible government," the next-to-last stage of preparation before the formal granting of independence. It was assumed that those winning the election would gain valuable experience in office, preparing them for the probable responsibility of governing after independence.

In Buganda the "King's Friends" urged a total boycott of the election because their attempts to secure promises of future autonomy had been rebuffed. Consequently, when the voters went to the polls throughout Uganda to elect eighty-two National Assembly members, in Buganda only the Roman Catholic supporters of the DP braved severe public pressure and voted, capturing twenty of Buganda's twenty-one allotted seats. This artificial situation gave the DP a majority of seats, although they had a minority of 416,000 votes nationwide versus 495,000 for the UPC. Benedicto Kiwanuka became the new chief minister of Uganda.

Shocked by the results, the Baganda separatists, who formed a political party called Kabaka Yekka (KY--The King Only), had second thoughts about the wisdom of their election boycott. They quickly welcomed the recommendations of a British commission that proposed a future federal form of government. According to these recommendations, Buganda would enjoy a measure of internal autonomy if it participated fully in the national government. For its part, the UPC was equally anxious to eject its DP rivals from government before they became entrenched. Obote reached an understanding with Kabaka Freddie and the KY, accepting Buganda's special federal relationship and even a provision by which the kabaka could appoint Buganda's representatives to the National Assembly, in return for a strategic alliance to defeat the DP. The kabaka was also promised the largely ceremonial position of head of state of Uganda, which was of great symbolic importance to the Baganda.

This marriage of convenience between the UPC and the KY made inevitable the defeat of the DP interim administration. In the aftermath of the April 1962 final election leading up to independence, Uganda's national parliament consisted of fortythree UPC delegates, twenty-four KY delegates, and twenty-four DP delegates. The new UPC-KY coalition led Uganda into independence in October 1962, with Obote as prime minister and the kabaka as head of state.

Uganda's approach to independence was unlike that of most other colonial territories where political parties had been organized to force self-rule or independence from a reluctant colonial regime. Whereas these conditions would have required local and regional differences to be subordinated to the greater goal of winning independence, in Uganda parties were forced to cooperate with one another, with the prospect of independence already assured. One of the major parties, KY, was even opposed to independence unless its particular separatist desires were met. The UPC-KY partnership represented a fragile alliance of two fragile parties.

In the UPC, leadership was factionalized. Each party functionary represented a local constituency, and most of the constituencies were ethnically distinct. For example, Obote's strength lay among his Langi kin in eastern Uganda; George Magezi represented the local interests of his Banyoro compatriots; Grace S.K. Ibingira's strength was in the Ankole kingdom; and Felix Onama was the northern leader of the largely neglected West Nile District in the northwest corner of Uganda. Each of these regional political bosses and those from the other Uganda regions expected to receive a ministerial post in the new Uganda government, to exercise patronage, and to bring the material fruits of independence to local supporters. Failing these objectives, each was likely either to withdraw from the UPC coalition or realign within it.

Moreover, the UPC had had no effective urban organization before independence, although it was able to mobilize the trade unions, most of which were led by non-Ugandan immigrant workers from Kenya (a situation which contributed to the independent Uganda government's almost immediate hostility toward the trade unions). No common ideology united the UPC, the composition of which ranged from the near reactionary Onama to the radical John Kakonge, leader of the UPC Youth League. As prime minister, Obote was responsible for keeping this loose coalition of divergent interest groups intact.

Obote also faced the task of maintaining the UPC's external alliances, primarily the coalition between the UPC and the kabaka, who led Buganda's KY. Obote proved adept at meeting the diverse demands of his many partners in government. He even temporarily acceded to some demands which he found repugnant, such as Buganda's claim for special treatment. This accession led to demands by other kingdoms for similar recognition. The Busoga chiefdoms banded together to claim that they, too, deserved recognition under the rule of their newly defined monarch, the kyabasinga. Not to be outdone, the Iteso people, who had never recognized a precolonial king, claimed the title kingoo for Teso District's political boss, Cuthbert Obwangor. Despite these separatist pressures, Obote's long-term goal was to build a strong central government at the expense of entrenched local interests, especially those of Buganda.

The first major challenge to the Obote government came not from the kingdoms, nor the regional interests, but from the military. In January 1964, units of the Ugandan Army mutinied, demanding higher pay and more rapid promotions (see The First Obote Regime: The Growth of the Military , ch. 5). Minister of Defense Onama, who courageously went to speak to the mutineers, was seized and held hostage. Obote was forced to call in British troops to restore order, a humiliating blow to the new regime. In the aftermath, Obote's government acceded to all the mutineers' demands, unlike the governments of Kenya and Tanganyika, which responded to similar demands with increased discipline and tighter control over their small military forces.

The military then began to assume a more prominent role in Ugandan life. Obote selected a popular junior officer with minimal education, Idi Amin Dada, and promoted him rapidly through the ranks as a personal protÉgÉ. As the army expanded, it became a source of political patronage and of potential political power.

Later in 1964, Obote felt strong enough to address the critical issue of the "lost counties," which the British had conveniently postponed until after independence. The combination of patronage offers and the promise of future rewards within the ruling coalition gradually thinned opposition party ranks, as members of parliament "crossed the floor" to join the government benches. After two years of independence, Obote finally acquired enough votes to give the UPC a majority and free himself of the KY coalition. The turning point came when several DP members of parliament (MPs) from Bunyoro agreed to join the government side if Obote would undertake a popular referendum to restore the "lost counties" to Bunyoro. The kabaka, naturally, opposed the plebiscite. Unable to prevent it, he sent 300 armed Baganda veterans to the area to intimidate Banyoro voters. In turn, 2,000 veterans from Bunyoro massed on the frontier. Civil war was averted, and the referendum was held. The vote demonstrated an overwhelming desire by residents in the counties annexed to Buganda in 1900 to be restored to their historic Bunyoro allegiance, which was duly enacted by the new UPC majority despite KY opposition.

This triumph for Obote and the UPC strengthened the central government and threw Buganda into disarray. KY unity was weakened by internal recriminations, after which some KY stalwarts, too, began to "cross the floor" to join Obote's victorious government. By early 1966, the result was a parliament composed of seventy- four UPC, nine DP, eight KY, and one independent MP. Obote's efforts to produce a one-party state with a powerful executive prime minister appeared to be on the verge of success.

Paradoxically, however, as the perceived threat from Buganda diminished, many non-Baganda alliances weakened. And as the possibility of an opposition DP victory faded, the UPC coalition itself began to come apart. The one-party state did not signal the end of political conflict, however; it merely relocated and intensified that conflict within the party. The issue that brought the UPC disharmony to a crisis involved Obote's military protege, Idi Amin.

In 1966 Amin caused a commotion when he walked into a Kampala bank with a gold bar (bearing the stamp of the government of the Belgian Congo) and asked the bank manager to exchange it for cash. Amin's account was ultimately credited with a deposit of £17,000. Obote rivals questioned the incident, and it emerged that the prime minister and a handful of close associates had used Colonel Amin and units of the Uganda Army to intervene in the neighboring Congo crisis. Former supporters of Congolese leader Patrice Lumumba, led by a "General Olenga," opposed the American-backed government and were attempting to lead the Eastern Province into secession. These troops were reported to be trading looted ivory and gold for arms supplies secretly smuggled to them by Amin. The arrangement became public when Olenga later claimed that he failed to receive the promised munitions. This claim appeared to be supported by the fact that in mid-1965, a seventy-five-ton shipment of Chinese weapons was intercepted by the Kenyan government as it was being moved from Tanzania to Uganda.

Obote's rivals for leadership within the UPC, supported by some Baganda politicians and others who were hostile to Obote, used the evidence revealed by Amin's casual bank deposit to claim that the prime minister and his closest associates were corrupt and had conducted secret foreign policy for personal gain, in the amount of £25,000 each. Obote denied the charge and said the money had been spent to buy the munitions for Olenga's Congolese troops. On February 4, 1966, while Obote was away on a trip to the north of the country, an effective "no confidence" vote against Obote was passed by the UPC Mps. This attempt to remove Obote appeared to be organized by UPC Secretary General Grace S.K. Ibingira, closely supported by the UPC leader from Bunyoro, George Magezi, and a number of other southern UPC notables. Only the radical UPC member, John Kakonge, voted against the motion.

Because he was faced with a nearly unanimous disavowal by his governing party and national parliament, many people expected Obote to resign. Instead, Obote turned to Idi Amin and the army, and, in effect, carried out a coup d'État against his own government in order to stay in power. Obote suspended the constitution, arrested the offending UPC ministers, and assumed control of the state. He forced a new constitution through parliament without a reading and without the necessary quorum. That constitution abolished the federal powers of the kingdoms, most notably the internal autonomy enjoyed by Buganda, and concentrated presidential powers in the prime minister's office. The kabaka objected, and Buganda prepared to wage a legal battle. Baganda leaders rhetorically demanded that Obote's "illegal" government remove itself from Buganda soil.

Buganda, however, once again miscalculated, for Obote was not interested in negotiating. Instead, he sent Idi Amin and loyal troops to attack the kabaka's palace on nearby Mengo Hill. The palace was defended by a small group of bodyguards armed with rifles and shotguns. Amin's troops had heavy weapons but were reluctant to press the attack until Obote became impatient and demanded results. By the time the palace was overrun, the kabaka had taken advantage of a cloudburst to exit over the rear wall. He hailed a passing taxi and was driven off to exile. After the assault, Obote was reasonably secure from open opposition. The new republican 1967 constitution abolished the kingdoms altogether. Buganda was divided into four districts and ruled through martial law, a forerunner of the military domination over the civilian population that all of Uganda would experience after 1971.

Obote's success in the face of adversity reclaimed for him the support of most members of the UPC, which then became the only legal political party. The original independence election of 1962, therefore, was the last one held in Uganda until December 1980. On the homefront, Obote issued the "Common Man's Charter," echoed the call for African Socialism by Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere, and proclaimed a "move to the left" to signal new efforts to consolidate power. His critics noted, however, that he placed most control over economic nationalization in the hands of an Asian millionaire who was also a financial backer of the UPC. Obote created a system of secret police, the General Service Unit (GSU). Headed by a relative, Akena Adoko, the GSU reported on suspected subversives (see Internal Security Services , ch. 5). The Special Force Units of paramilitary police, heavily recruited from Obote's own region and ethnic group, supplemented the security forces within the army and police.

Although Buganda had been defeated and occupied by the military, Obote was still concerned about security there. His concerns were well founded; in December 1969 he was wounded in an assassination attempt and narrowly escaped more serious injury when a grenade thrown near him failed to explode. He had retained power by relying on Idi Amin and the army, but it was not clear that he could continue to count on their loyalty.

Obote appeared particularly uncertain of the army after Amin's sole rival among senior army officers, Brigadier Acap Okoya, was murdered early in 1970. (Amin later promoted the man rumored to have recruited Okoya's killers.) A second attempt was made on Obote's life when his motorcade was ambushed later that year, but the vice-president's car was mistakenly riddled with bullets. Obote began to recruit more Acholi and Langi troops, and he accelerated their promotions to counter the large numbers of soldiers from Amin's home, which was then known as West Nile District. Obote also enlarged the paramilitary Special Force as a counterweight to the army.

Amin, who at times inspected his troops wearing an outsized sport shirt with Obote's face across the front and back, protested his loyalty. But in October 1970, Amin was placed under temporary house arrest while investigators looked into his army expenditures, reportedly several million dollars over budget. Another charge against Amin was that he had continued to aid southern Sudan's Anya Nya rebels in opposing the regime of Jafaar Numayri even after Obote had shifted his support away from the Anyanya to Numayri. This foreign policy shift provoked an outcry from Israel, which had been supplying the Anyanya rebels. Amin was close friends with several Israeli military advisers who were in Uganda to help train the Ugandan Army, and their eventual role in Amin's efforts to oust Obote remained the subject of continuing controversy.

![[JPEG]](/africa/ug/ug01_05a.jpg) |

Idi Amin addresses the United Nations General Assembly in New York, October

1975.

Courtesy United Nations (T. Chen)

By January 1971, Obote was prepared to rid himself of the potential threat posed by Amin. Departing for the Commonwealth Conference of Heads of Government at Singapore, he relayed orders to loyal Langi officers that Amin and his supporters in the army were to be arrested. Various versions emerged of the way this news was leaked to Amin; in any case, Amin decided to strike first. In the early morning hours of January 25, 1971, mechanized units loyal to him attacked strategic targets in Kampala and the airport at Entebbe, where the first shell fired by a pro-Amin tank commander killed two Roman Catholic priests in the airport waiting room. Amin's troops easily overcame the disorganized opposition to the coup, and Amin almost immediately initiated mass executions of Acholi and Langi troops, whom he believed to be pro-Obote.

The Amin coup was warmly welcomed by most of the people of the Buganda kingdom, which Obote had attempted to dismantle. They seemed willing to forget that their new president, Idi Amin, had been the tool of that military suppression. Amin made the usual statements about his government's intent to play a mere "caretaker role" until the country could recover sufficiently for civilian rule. Amin repudiated Obote's nonaligned foreign policy, and his government was quickly recognized by Israel, Britain, and the United States. By contrast, presidents Julius Nyerere of Tanzania, Kenneth Kaunda of Zambia, Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya, and the Organization of African Unity (OAU) initially refused to accept the legitimacy of the new military government. Nyerere, in particular, opposed Amin's regime, and he offered hospitality to the exiled Obote, facilitating his attempts to raise a force and return to power.

Amin's military experience, which was virtually his only experience, determined the character of his rule. He renamed Government House "the Command Post," instituted an advisory defense council composed of military commanders, placed military tribunals above the system of civil law, appointed soldiers to top government posts and parastatal agencies, and even informed the newly inducted civilian cabinet ministers that they would be subject to military discipline. Uganda was, in effect, governed from a collection of military barracks scattered across the country, where battalion commanders, acting like local warlords, represented the coercive arm of the government. The GSU was disbanded and replaced by the State Research Bureau (SRB; see Idi Amin and Military Rule , ch. 5). SRB headquarters at Nakasero became the scene of torture and grisly executions over the next several years.

Despite its outward display of a military chain of command, Amin's government was arguably more riddled with rivalries, regional divisions, and ethnic politics than the UPC coalition that it had replaced. The army itself was an arena of lethal competition, in which losers were usually eliminated. Within the officer corps, those trained in Britain opposed those trained in Israel, and both stood against the untrained, who soon eliminated many of the army's most experienced officers. In 1966, well before the Amin era, northerners in the army had assaulted and harassed soldiers from the south. In 1971 and 1972, the Lugbara and Kakwa (Amin's ethnic group) from the West Nile were slaughtering northern Acholi and Langi, who were identified with Obote. Then the Kakwa fought the Lugbara. Amin came to rely on Nubians and on former Anya Nya rebels from southern Sudan.